This poem arrived on a morning when the world felt …tilted — muscle and memory moved just that smidge faster than thought. On its own, perhaps it stands as the first record of the body’s response to sudden loss, and the entry point into the reflections and research that follow.

Readers who recognise themselves in these moments — the reaching, the breath catching, the sudden illness — may find a sense of companionship in what comes after.

I woke this morning,

felt as if you were lying next to me

but —

wrong light, wrong shadows;

The shades of quoshed pillows,

irreverent 10.5 tog duvet

pulled this way and that,

the stripes of the

duvet cover

akimbo.

Mid-reach

I knew

KNEW

it wasn’t true—

you’re not

HERE

but I

reached out anyway

just

in

case …

My fingers landed

on cold pillows.

My heart’s

hopes ruptured—

spurting like

a punctured artery.

The crumpled duvet

found a twin

on my face—

a nano second

before

ugly crying began.

This poem records one moment of a pattern that repeats itself quietly throughout bereavement. The body carries decades of shared life in its own private, deeply interwoven architecture, and these structures do not collapse the same day he died.

I write this for those who understand that experience — the bereaved who continue to push themselves to maintain agency, think clearly, push on to organise, to care for others, and all the time inexplicably feel the physical body falter in unexpected ways.

1. Grief as a Physical Event

Grief moves through the body in instinctive ways. After sudden loss, the nervous system shifts: breathing shortens, the heartbeat unsettles, sleep is thin. Hypervigilance sets in — a heightened sensory field, the body scanning the room, attuned to sound and light, sudden movements.

The body is trying to comprehend a world it can no longer map (Knowles et al., 2019).

2. Immune Dysregulation and Recurrent Illness

I’m sick again. Coughs and colds cycling back—the body’s immune system compromised by months of elevated cortisol and disrupted sleep. Five days in crowds, and now I’m in bed, fighting infections my body would have shrugged off before. Research shows bereaved individuals demonstrate higher levels of systemic inflammation, maladaptive immune cell gene expression, and lower antibody response to vaccination compared with non-bereaved controls (Knowles et al., 2019).

3. Grief Across Multiple Bodily Systems

Sleep fractures. Non-existent appetite. The chest tightens. The stomach knots. Studies document high prevalence of sleep disturbances in bereavement, with positive associations between grief intensity and sleep difficulties persisting well beyond six months (Lancel et al., 2020). Stress-related cardiac disturbances during bereavement are clinically documented, with bereaved individuals showing significantly elevated mortality risk in the first week following loss, particularly from cardiovascular causes (Chen et al., 2022).

4. The Administrative Aftermath and Sustained Stress

Alongside interior upheaval, bereavement demands sharp, focused labour in death administrations: probate, pensions, financial notifications, institutional forms. These tasks require precision on days when concentration feels thin.

The nervous system remains tense long after the paperwork is complete. Thinking clearly through grief requires its own form of stamina.

5. Duration and Persistence Beyond Six Months

Cultural expectations suggest improvement after several months. Yet biological evidence shows that disruptions can persist long beyond that point. Immune dysregulation, sleep disturbance, and inflammatory responses may continue for months or years following spousal bereavement (Knowles et al., 2019; Lancel et al., 2020).

6. Attending to the Grieving Body

A few steadying measures help — though on some days they feel impossible, and on others, barely enough.

Sleep: Gentle routines help regulate the body’s responses. I walk up and down the stairs before bed, the repetitive movement helping to settle the vigilance. On more active days, I manage to row for 10 minutes. The machine sits in the corner, sometimes used, sometimes ignored for weeks. The point is not perfection. The point is offering the body something rhythmic when it cannot find rhythm on its own.

Nutrition and Movement: Grief unsettles appetites and rhythms. Small, consistent steps help re-anchor the system. Friends pop over to make sure I eat. They bring soup. They sit with me while I manage three bites, then six. Some days I forget meals entirely until someone texts: “Have you eaten?” The kindness of being monitored without judgment — this matters more than the food itself, though the food matters too.

These threads of support — rest, nourishment, and human steadiness — carry more weight than they appear to.

7. Concluding Reflection

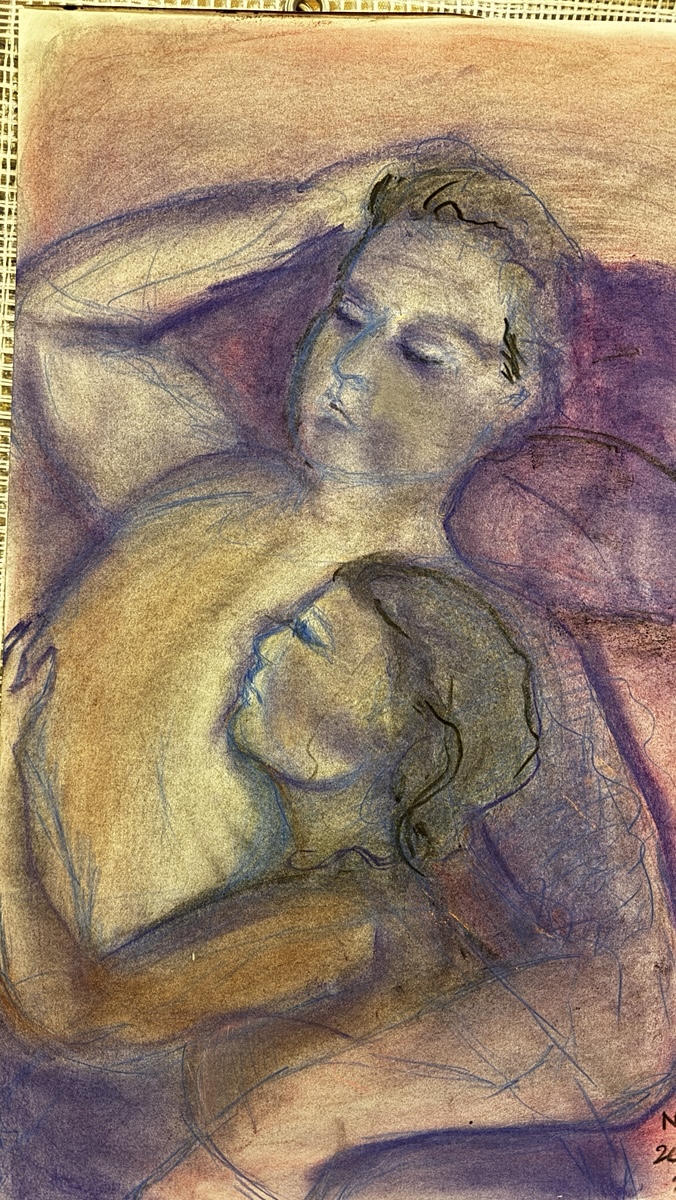

This piece is for those who grieve — those who wake at 3 a.m., 4 a.m., reaching across before they’re fully conscious. The poem marks one such moment, where instinct reaches toward someone who is no longer present.

My own longing remains sharp. It rises at 6:15 a.m., the time Greg used to wake. I hear phantom footsteps on the hallway. I turn toward the kitchen expecting him, then remember. Some afternoons I stop mid-task, realising I’ve been listening — for his key in the door, for his voice calling up, for the particular sound of him moving through rooms. The body keeps vigil even when the mind knows better.

In the harder passages of the day, others hold me upright. A friend texts: “Thinking of you today.” Another drops off dinner without needing to be asked. The neighbour knocks with coffee, stays for twenty minutes, asks nothing of me. These small acts — unscheduled, unrequested — calm the vigilance. They remind me that the world, though fundamentally altered, still contains safety.

Caring for the body during grief is part of continuing. The rowing machine, the stairs walked up and down, the soup accepted, the sleep attempted — these are not solutions. They are scaffolding. Attention, patience, and companionship create the structure that carries thought, work, and breath. Capability remains — reshaped by loss but still steady beneath it.

And beneath the ache, beneath the fatigue, beneath each morning when I wake and remember again, there is still a person here. Someone who remembers our kitchen dance, who loves him fiercely still, who steps — slowly, sometimes stumbling, but deliberately — into whatever comes next.

This is the science. Now here is what that science cannot measure:

He is my home.

No, not as mere metaphor. I mean in the physical sense: the man whose presence steadied the rooms, steadied my breath, steadied the shape of my days. With him in the house I worked easily, without the low hum of vigilance that shadows me now. When he entered a room, my shoulders settled before I even turned to look.

I learned that the term ‘attachment’ is what we had. This, in adults, is the mechanism by which one person becomes the most reliable source of safety, the co-regulator of stress, the primary emotional home, and the person the body rests around (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2022).

Our life was simple in its architecture. Weekdays I cooked; weekends his turn. The kitchen was our shared terrain during lunch hour when we both worked from home— the small “kitchen dance” of stepping aside, reaching past, trading spaces without speaking.

He would call up, stretching out my name in playful, singing tones: “Nuuu-uuusye, would you like some cofffeeee?” Our private language. The playful, adorable version of himself he’d be mortified for anyone else to witness. He was, like me, deeply private in our ease with each other. We kept us private, and I loved him for it. I am so much in love with him still.

When I wandered for hours through galleries — lost in William Blake’s visions, studying etching lines and mythic imagery, or Sargent’s forms — he waited for me with, what I now realise, the patience of a man who loved without conditions. I would find him seated somewhere, headphones in, watching rugby on his phone, content in the knowledge that I would return when I was ready. And he would be there. Always.

His rugby, my art. Two worlds. One orbit. We were separate in interests, joined in our comfort and ease.

Rugby days at Twickenham or Cardiff were for him. I’ve not got round to understanding the finer points of the rules. I didn’t need to. What I understood was the way his joy pulled the tension out of the day. I went because I enjoyed watching him, feeling his happiness enjoying the game. It mattered how he was moved by the game, immersed in it, and being near a happy Greg was enough.

We weren’t spectacular. We weren’t the beautiful, gorgeous couple. We just weren’t. Ours was the kind of companionship that becomes invisible while you live it — and entirely unimaginable to lose.

Now the house holds its shape, but the atmosphere is altered. I sit in his chair now, the one that faces the television. I curl into the cushion that still holds the shape of him. I stand where he stood in the kitchen, making coffee the way he made it, stretching out the ritual. These are not shrines. They are the places I go to find him.

The evenings are longest. Between 6 and 7pm, when he would have been home, I occupy his spaces deliberately. I sit at his desk. I touch his gadgets. The tablet he used to watch rugby on — I hold it sometimes, just to hold something he held. This is how I keep him close, by inhabiting the rooms he inhabited, by claiming the air he moved through.

The silence isn’t empty. It’s full of his memories. The world remains — the walls, the furniture, the bed with its striped duvet. But the sense of home has moved into these small acts of occupation: sitting in his chair, standing in his kitchen spot, reaching across the bed not because I forget, but because reaching is how I remember.

I love him very much.

I am still in love with him.

That is the truth I have.

Nusye McComish – SouthSeaEyes Printmaker

Footnotes

RESEARCH SOURCES :

For immune dysregulation:

* Knowles, L., M., Ruiz, J.M., & O’Connor, M.F. (2019). A Systematic Review of the Association Between Bereavement and Biomarkers of Immune Function. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81(5), 415-433. PubMed Central

For cardiac/stress cardiomyopathy:

* Chen, H., Wei, D., Janszky, I., et al. (2022). Bereavement and Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Swedish Cohort Study. JACC: Heart Failure. ScienceDaily

For sleep disruption:

* Lancel, M., Stroebe, M., & Eisma, M.C. (2020). Sleep disturbances in bereavement: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 53, 101331. ScienceDirect

For attachment theory in spousal bereavement:

* Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P.R. (2022). An attachment perspective on loss and grief. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101283. ScienceDirect

For prolonged grief duration:

* Hall, M., & Reynolds, C.F. (2014). Sleep disturbances and bereavement. In Sleep and Affect (pp. 223-245). PubMed Central